Blog #29 Who is Likely to Die in War? Survive?

Who Is Likely To Die in War?

I read an essay by a former soldier of the German Army who fought in Kosovo. His story is attached at the end of my comments. It made me think of my own experience as an Army infantry platoon leader in Vietnam. I have a perspective to share with you about who will die and who will survive. Please consider these situations/lessons as they apply today, when not in a war.

Some background: After graduating from the University, I volunteered to go to war in 1968 at the height of the Vietnam War. During the first half of 1968, major battles were being fought, the most famous being the Tet Offensive. Every week, Walter Cronkite would announce the casualties, and up to 500+ were killed and thousands wounded (again, weekly!)

No matter, no fear. I was going to serve to save American lives and kill as many of the enemy as I could. Yes, I was so young and naïve, but I was motivated. However, it was vital for me to have time to mature after high school, and college gave me that time to mature and qualify for Officer Candidate School (OCS) to be an officer. I sincerely felt that I could make a difference with small unit warfare.

After basic and advanced infantry training, I volunteered for Jump School to be a paratrooper. This gave me a sense of controlling my fears. I went home at Christmas, got married, and then brought my wife back to Fort Benning. Then on to OCS to become a Lieutenant. After OCS, I spent seven months as a training officer, and our son was born three months before I left for Jungle Expert Training School at Fort Sherman, Panama Canal Zone. Next was my long trip to Vietnam.

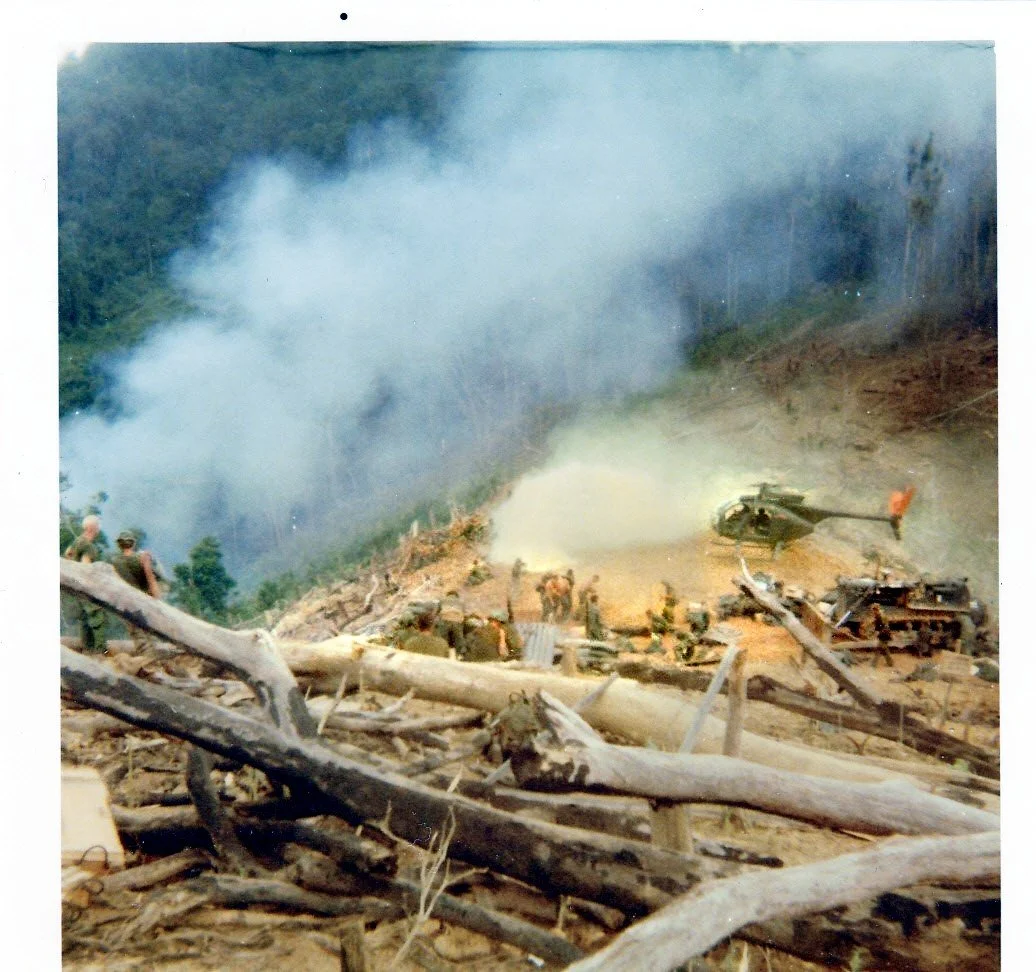

After two years of outstanding training (I volunteered for all the training I could get which was important to my survival), I was helicoptered/Huey out to Hill 251 west of Hawk Hill, a large firebase northwest of Chu Lai. Yes, I was an "FNG" or fucking new guy. Respect would have to be earned.

I would learn after the war that infantry Lieutenants had the highest death rate by rank in the entire war.

I was supposed to "look, listen, and learn" while following the Lieutenant who had four months of experience in-country leading the third platoon for Bravo Company. In the first couple of hours on my first patrol after arriving in Vietnam, walking in a single file across rice paddies, the world blew up.

I was blown backward and submerged under the putrid, brown rice paddy water filled with disgusting creatures and feces. I frantically checked my body to see if I was injured. I hear screaming and soldiers racing around. Then my thoughts raced to the realization that in my first couple of hours on my first patrol after arriving in Vietnam, I almost got killed. I asked myself, how could I last a year?

The Lieutenant and the radioman were severely injured, crippled for life. Why? The Lieutenant did not listen to the Company Commander's instructions to follow the map that would keep us out of a mine field. Even with experience, he let his guard down and became complacent. Yes, he was exhausted from months in the rice paddies and assumed he would be okay since there were no sightings of the enemy.

Forced to take over the platoon immediately, I asked questions and tried to learn without being an arrogant know-it-all. (Little did I know that shrapnel had pierced my lower leg, and I never noticed it with my jungle fatigue pants tied down around my boots as I slogged through the rice paddies.) I kept my head on straight and moved quickly.

Weeks would go by as we penetrated deeper into enemy territory. No matter how careful we were, more men were wounded and killed by booby-traps. The enemy was very skilled at setting these traps that could take off your feet, legs, or worse. Even so, I took each loss as my personal failure, and it rocked me every time, prompting me to think harder and act faster to avoid the traps.

Some would die not because of physical strength, skill, or intelligence but by sheer luck and circumstance.

For me, training was crucial for my survival for several proven reasons. You have to respect danger for what it is, for what you must expect, and not to underestimate. I always viewed the enemy as competent. Therefore, I had to anticipate their moves and mine. Yes, some soldiers looked down on the enemy as puny incompetents. They weren't!

Knowing where you were by diligently reading the map/compass was life or death. That is true in life: have a clear purpose and know where you are going and why.

Anticipating where you could be ambushed and knowing how to respond if caught – that will save lives. One must know how to act assuming worst-case scenarios. Having a backup plan inspires confidence.

So, beyond motivation, discipline, and training, I cannot overstate the requirement in war and in life to anticipate, anticipate, and anticipate.

If a surprise happens, what then do I do? I asked that question every few feet during a patrol. I was always alert. No way can you relax during an operation, no matter the circumstances. Complacency kills.

I would not say I was seeking revenge, but I was mindful that my job was to kill the enemy and not lose any of my soldiers in the process. An example of this was during a patrol deep in enemy territory near the Laotian border and the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was thick with jungle. After engaging the enemy and killing half a dozen of them, I was ordered to go deeper into the jungle and seek them out.

At one point, while moving slowly, my point man opened fire on the point man of an enemy squad approaching us on the same path. It was a "first-to-fire wins" situation. (We were taught "quick kill techniques in training). Both opened fire at the exact moment. My soldier was shot 6 times in non-life-threatening areas of his body. The enemy was shot once in the head and killed—the rest of the enemy scattered.

After putting him on a Medivac (he was smoking a cigarette and laughing that he was going home), I was ordered to continue cutting through the jungle to seek contact with the enemy. After some time, I stopped to rest and decided on my next course of action. My guys were exhausted from the heat, the strain of carrying all our gear, and the effort of cutting through thick vegetation. The call came over the radio asking about my progress. A sergeant rushed up to me with others supporting his pleas. He pleaded with me that the enemy knows where we are. We could walk into an ambush. I overruled my desire and my commander's order to continue, deciding not to take a risk that was not in our favor.

Decisions are about risk. In war, you must always be aggressive, but generally not when you are at a serious disadvantage. We all take risks; some are reckless, some are calculated. Knowing the difference is a life-or-death perspective.

Of the 23 soldiers in my platoon, nearly half were drafted and were less than 20 years of age. Except for a supply sergeant who did not come out to the bush, I was the oldest at 23. The less disciplined they were, the more likely they were to get hurt. No matter how much training you get, if the lessons are not practiced, trouble follows.

In one example, after weeks of patrols and contact that kept us on edge, we hooked up with our Company in a large, circular position for nightfall. We entered the perimeter, and I ordered them to start digging foxholes at their assigned position. My machine gunner was exhausted, dehydrated, hungry, and bitter about the war, and jumped into an old, shallow hole, which ignited a massive explosion. Only his upper, blackened torso was left. Six others were wounded. When you are weakest, you are likely to make an irreversible mistake.

Controlling fear is very difficult. After several weeks with frequent firefights with the enemy and the loss of a couple of my soldiers, a young replacement (FNG) private was flown out to join my platoon. Within an hour of hearing about the platoon's exploits from guys sharing the stories, this FNG walked over to a bunker, pointed his M-16 at his shoulder, and pulled the trigger. He was just too terrified about going out in the jungle.

When we caught the enemy being complacent or stupid, he would die. Some believed that in a thick jungle, following a familiar trail at night would be safe enough. However, we anticipated that they would try that, and they lost.

In any competition, anticipating what your opposition will do is critical to your survival in war, or success in sports, or profit in business.

During one battle, my platoon surprised a squad of enemy soldiers dug in with foxholes at the top of a hill. We saw them first. We slowly moved in the jungle around to a point where we could rush the hill, but only after I called in the "FireBirds" (helicopter gunships) to rake the hill with cannon and machine gun fire. After the last gun run by the choppers, we launched an aggressive "John Wayne" attack, and we won. We killed several of the enemy and saw blood trails into the jungle while abandoning their weapons, including a machine gun. None of my men was injured. I was so full of adrenaline that a sergeant had to calm me down. But it showed good planning, positioning, and coordination as a team.

On another occasion, I wanted to call in artillery to kill the enemy. But the fire coordinates have to be perfect. If not, friendly artillery fire could be worse than the enemy's small arms fire. We were in the jungle with no visible landmarks. Well, even as we were taking gunfire, I had to admit to myself that I could not be 100% sure, and I called off the fire mission with the artillery battery. The enemy was too close. I thought I could be smart and deal a death blow, but it could have been a disaster instead.

Although I persistently sought out the enemy, I was not aggressively dangerous with lives for a war that was very difficult for many reason and with many restrictions: locating the enemy, no border crossings, knowing who to shoot, free fire zones vs non-free fire zones, innocent civilians in free fire zones, an enemy without uniforms, and it being a pure guerrilla conflict for several months before going out on the Laotian border to deal with North Vietnamese regular army soldiers (NVA) .

Knowing what your target is can make or break your day. During a patrol in a free fire zone, we were walking alongside a river with thick bushes along the riverbanks. Suddenly, we heard lots of movement in the bushes, and instinctively, a dozen soldiers opened fire, indiscriminately raking the area instantly. We soon learned we had killed a water buffalo. While that was a joke, on another occasion with a very similar situation, the point man opened fired and we learned it was two young boys playing hide and seek in black pajamas. War is tragic.

It was a time when everyone in the "bush" or field had to "mentally be on" and "alert" all the time, night and day, every day. Even so, skill, focus, discipline, and courage were demanded but not a guarantee. In the end, my own survival, after being wounded twice, was also about being blessed by God, having a purpose to go home to my wife and son, and just being lucky. We live by our choices. Making the right choices is not easy.

My decision to volunteer for the Army to fight in Vietnam, since I survived and did not lose a part of my body or get a disease from Agent Orange, was not only a defining moment, but it made me a better man with tempered fears and ready to tackle new challenges.

I must agree with all of the comments below by Roland Bartetzko, but especially these:

“Surprisingly, the brave ones, the hero types, don't die more often than the more careful soldiers. I think this is because they are less inhibited by fear and have a clearer mind. Sometimes, a quick decision and a daring move are exactly what you need to get yourself out of a dangerous situation.”

John Shoemaker, LT, 3rd Platoon, Bravo Company, 2nd Battalion, First Infantry, 196th Light Infantry Brigade, Americal Division in I Corps, Vietnam. 1970.

What types of people die at war? Why?

Roland Bartetzko, former German Army, Croatian Defense Council, Kosovo Liberation Army • Answered December 8, 2019

What types of people die at war? Why?

This may sound like BS and I have no empirical evidence to support my observations, but in both wars I fought, there were certain types of soldiers that died more often than the others:

· Soldiers that take the whole war personally. If you think that you are on a personal vendetta against your enemy, maybe because they killed someone of your family, you lower your chances to survive. Your decisions won't be based on reason and you'll take unnecessary risks.

· The ones that don't have a clue what's going on. These are often, but not always, the newbies, the inexperienced.

· People that are easily scared. Fear plays havoc with your ability to properly judge a situation. You are in a well-built position, but when the enemy attacks, you panic, run outside and get yourself shot.

· Naïve and immature people. The "kids" often get themselves killed. You see people on the frontline who really shouldn't be there. They still haven't figured out what it means to be in a war and that they can die. They might be good soldiers who master all the combat skills, but they tend to believe everything their superiors are telling them and completely lack critical thinking. Sometimes, however, it's necessary to discard what other people are telling you and make up your own mind.

What all these people have in common is that they misjudge the situation. This is much more dangerous than when you are a bad shooter or completely out of shape.

Surprisingly, the brave ones, the hero types, don't die more often than the more careful soldiers. I think this is because they are less inhibited by fear and have a clearer mind. Sometimes, a quick decision and a daring move are exactly what you need to get yourself out of a dangerous situation